New York Herald Tribune, Paris, Friday, March 13, 1964 – Page 9

AMERICA’S CUP FORMULA INCLUDES MONEY, GENIUS, CRAFTSMANSHIP, PATRIOTISM

By Anthony Bailey- from the Herald Tribune Bureau

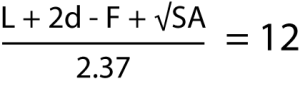

New York. – The formula that defines the Twelve Metre class of racing yachts, the class that will compete in the America’s Cup matches coming up in September, is expressed by the equation:

Which takes into account such factors as length (L), skin girth and chain girth (d), sail area and freeboard. It might just as well be expressed: money, plus genius, plus craftsmanship, multiplied by X (which includes desire for fame, love of the sea, patriotism, competitiveness, etc.).

Which takes into account such factors as length (L), skin girth and chain girth (d), sail area and freeboard. It might just as well be expressed: money, plus genius, plus craftsmanship, multiplied by X (which includes desire for fame, love of the sea, patriotism, competitiveness, etc.).

The money and the X-factor are where the yacht begins, as you can see in Walter Gubelmann’s pink-walled office on the 19th floor of the Seagram Building, the Twelve-Meter of Park Avenue towers. Over the couch there is a painting of Windigo, Gubelmann’s crack 70-foot ocean-racing yawl. On a side table rests a leather-bound volume of clippings concerning Seven Seas, the three masted, square-rigged ship that belonged to Gubelmann pere (inventor of adding and subtracting machines), and on which with 27 crew, Walter Gubelmann as a young man raced young Huntington Hartford’s Joseph Conrad, the only other privately-owned square rigger at hand. Next year there may well be a scrapbook and a portrait of Constellation, a new “Twelve” designed as a candidate to defend the America’s Cup against the British this fall.

Working Name

“Constellation is only the working name, mind you,” says Gubelmann, with the air of a man constantly balanced between reservation and decision. “We can change it at any time up the launching.” Constellation was also the name of the United States frigate, nicknamed “The Yankee Racehorse,” which the British blockading fleet kept bottled up in Hampton Roads through the entire War of 1812, but for all that, it isn’t a bad name for a syndicate-owned craft that will cost roughly $500,000 to design, build, equip and campaign for one sailing season on Long Island and Block Island Sounds.

I’ve been thinking about the America’s Cup since 1957, without doing anything about it,” Gubelmann said recently. “Then last summer there seemed to be a great lethargy over here in the face of what appeared to be a very serious British challenge. They haven’t won back the Cup in nearly a century of trying, but for 1964, they are trying harder than ever. And we were resting on our laurels after the workout the Australians gave us in ’62.

My crew on Windigo talks about it. The New York Yacht Club is in charge of the Cup and its defense, and when I talked to the people there, they said: “Go ahead, the more contending boats we have the better.” So I went to Delphi, that is to Harold Vanderbilt. He twice defended the Cup successfully — once with an inferior boat— against the British the 1930s. Mr. Vanderbilt said he would take a share if I formed a syndicate. That did it— I felt pretty good.

Safety Margin

“Well they say you need $500,000 and we’ve now got a little more than that— call it a safety margin. I have friends in Philadelphia, people we sail with in Main in summer. I have friends in Palm Beach, where I’ve lived half of my life. I’m afraid I have friends who are also Pierre du Pont’s friends, but he denied to build a new Twelve a littler later than we did, and I got to them before he did. All told, 25 people put up roughly $25,000 each. Eric Ridder, publisher of “The Journal of Commerce” and a great pal of mine in Oyster Bay, took a share. So did his father, and his brother.

“Some people gave me a check for the whole amount— one said he never bought anything on the installment system, and wouldn’t start now— but others are paying over six or eight months. Of course, there were those who said they’d take a share then after talking with their financial advisers, found they couldn’t. It’s not tax-deductible.

Gubelmann is syndicate manager and originally had himself slotted as the Constellation’s navigation. “I’m out for the job,” he had said, “but if I start making mistakes or if someone better turns up, I’m through. That goes for everyone on the boat.” Gubelmann meant what he said. Two weeks ago, he relieved himself of his navigator’s berth in favor of K. Dunn Gifford.

The Details

There remains, for Gubelmann, more than enough to do. The pre-war Twelve Nereus has been chartered as Constellation’s sparring partner, and Briggs Cunningham’s powerboat Chaperone will act as tender to the engine-less yachts. The Castle Hill Hotel, overlooking the entrance to Newport’s harbor, has been rented for a campaign base. Among other details to arrange was a $1,000,000 / $2,000,000 insurance policy to cover any boat used and a $1,000,000 / $3,000,000 umbrella policy to cover everything else, from a car a crew member may borrow, to slander.

About the design Gubelmann had no worry. There are fewer than a dozen naval architects in America with the experience and skill to take the Twelve-Meter formula and produce a successful Twelve-Meter yacht. Philip Rhodes, designed Weatherly, the last champion, and A.E. (Bill) Luders, who is designing the new du Pont boat, Aurora, worked on Weatherly’s modifications. Ray Hunt designed Easterner, which has never been raced steadily enough to show whether her occasional flashes of brilliance could, in other hands, be made more than occasional.

There are a few other naval architects, like Bill Tripp and Charles Morgan, who are waiting and willing, because the job is, of course, the plum of the profession. When the time came, however, Gubelmann chose Olin Stephens. “I don’t mean any disrespect to the other designers,” he said cautiously, “but we know Olin Stephens and his brother, Rod. They designed Windigo 17 years ago. We felt a little closer to them.”

Renewed Interest

Olin Stephens once wanted to be a good painter, and studied under Heliker and Kuniyoshi. But he lacks the conventional “artistic” appearance. With brown suit, bow tie, glasses, a quiet, efficient manner, he might be a foreign service career officer, or a scholar of the medieval history he enjoys reading. Running the world’s largest yacht design firm ties him down to his office on lower Madison Ave. most of the time. What leisure he has is spent on his farm in Sheffield, Mass. And he doesn’t own a boat.

But Stephens regards any view of himself as disinterested in boats as either exaggerated or somewhat out of date. “There was a time, during the war, after it, and through the Korean affair when we did a lot of Navy work. I was busy running the office, keeping men employed, doing stacks of paperwork and I didn’t have much time for yacht design. But then all that slacked off, and the America’s Cup matches were revived. The commission to design Columbia party my interest again. When Mr. Gubelmann asked me if I would design a new Twelve, naturally, I said yes.” Stephens is not the man to point out that he is ta most logical choice to design a boat for a new America’s Cup defense, and that on that assumption he ad already been doodling with and pondering the design. Once commissioned, he spent three involved months with “the tank.” Stephens was the first yacht designer to tank-test hull models.

Stephens Institute

He helped Dr. Kenneth Davidson develop the research facilities at Stevens Institute of Technology in Hoboken, which are the best in the world, and indeed his identification with the place and the similarity of the names is such that foreign journals occasionally describe his boats as designed by the Stephens Institute. There, six-foot-long models costing $1200 each are put through various tests to determine resistance, lateral force, and leeway angle. The trials are also a test of accuracy; before the 1958 series, the Davidson lab found that dust collecting on models overnight could cause a one percent error in model resistance. For this series David Boyd, the British designer has also used the Hoboken tank, so the advantage has not been all Olin Stephens’s.

The Cup rules are being tightened, however, and after this year all design work including tank-testing will have to be done in the challenging country.* England by then will have an adequate take of its own. Any other country, such as Australia and Italy, will be seriously handicapped, since they have no such facilities. Stephens is worried about this. He says: “I used to think Twelve-Metre design was just a matter of refining what we already knew. The rule is very tight. But I’m beginning to think there are areas in which breakthroughs can be made. The tank has made this knowledge possible— it has shown, I think, that the V-sectioned keel is an advantage, and it should be able to show us a lot more.”

Computers in Future

“Soon I intend to start using a computer. Of course, you have to know what questions to ask a computer or a tank, and the tank isn’t perfect— it makes mistakes, which might lead a designer astray. And it can’t possibly show you every condition a yacht gets into. Although we have rough water arrangements at Hoboken, they provide primarily for taking the seas head-on and that isn’t entirely satisfactory.”

The best of Stephen’s series of models provided the hull lines for Constellation and with that conclusion the first and biggest of his headaches was over. The construction has to be supervised. Rig, sails and gear arrangements have to be made. But a Twelve-Metre’s function is entirely speed— to comply with the rule and win races— and the designer doesn’t have to make the compromises instead upon by cruising boat owners.

Human, Fallible Crew

He doesn’t have to worry about— though he probably will— the time to come when Constellation will be out of his hands and in those of a human, fallible crew. Crew— brilliant on Weatherly, middling on Columbia— was a big reason why a Stephens boat did not defend the Cup in 1962. There is always a chance that his boat may have the edge inherent ability, and the helmsman of the opposing craft emerge as a Vanderbilt or a Mosbacher.

These anxieties, at any rate, are premature. They concern the late summer days in the Brenton Reef swell of Newport, and not the winter mornings, twice a week when Olin Stephens and his brother Rod, the firm’s field engineer, drive out to City Island to call in at Minneford’s the yard where Constellation is building.

Minneford’s has in addition to its own men many of the skilled craftsmen who built Columbia at the now shut-down Nevins yard next door. Paul Coble, who was Stephen’s man-on-the-spot at Nevins in 1958 is assistant superintendent at Minneford’s. Nils Halvorsen who lofted Columbia, is doing the same for Constellation. He is a small, elderly Norwegian, springy and close-grained, a man who has spent a long life in company with good wood.

The Maze

A few weeks ago Constellation was still on the loft floor at Minneford’s. There are huge sheets of plywood, covered with a maze of black crayoned curves and diagonals and, as Nils Halvorsen points them out with a batten, they begin to form three views the craft: to one side the sections, as seen from down and stern, a wine-glass with no base; the rest, nearly 70 feet long, the profile and plan view superimposed, which can be disentangled to look something like a boat or a bullet.

These are Constellation’s lines, life-size, as drawn by Nils Halvorsen from the architect’s 3/4-inch-to-the-foot scale plans. It is a job for a craftsman, because no matter how accurate the designer is when he draws the yacht on a drawing table, there are bound to be places in the scale of 70 feet where one dimension will not coincide with another— where, if the boat were built that way, a rib might be too narrow by several inches or planking might be forced to take an “unfair” curve. And when he finds these gaps of an inch or two between one plane and another, points to where section and plan do not quite intersect, Nils Halvorsen either “fairs in” the curve between them, using his own judgement, or if it strikes him as an especially crucial spot, he calls up Olin Stephens.

Breakthrough

When Stephens talks about “breakthroughs” he is thinking in terms of changes of a fraction of an inch here and there. Fractions here and there are the difference between a winner and a loser. Bill Luders and David Boyd, the British designer, might be able to look at those lines and see in which direction Stephens has gone, and they would probably like to; but for most it is guesswork, with guesses based, perhaps, on Gretel’s down-wind ability and Weatherly’s stiffness— has Constellation a little more flare in the topsides than Columbia? Is there a triple more flatness in her run aft?

Once in a while, there is a reminder that you shouldn’t take it too seriously. Yachting is a sport. Boats are boats, though this is very much an ultimate boat, designed to furnish not only the maximum of completion to any challenger, but the most response to wind and sea as well. Quite possibly a form of masterpiece, a work of art. To that suggestion Olin Stephens returns a shrug and a laugh. “I don’t know. It’s just a question of doing your best.” Together with Paul Coble, Nils Halvorsen, and Walter Gubelmann, he hopes that his best is good enough to defend the Old Mug against the British Twelve, and that Constellation, if she is chosen, won’t be the first in the long history of the match to let the side down.

*The Australian challenger Gretel, tank-tested in Hoboken, outfitted with Hood sails, and probably a faster boat than Weatherly seems to have worried the New York Yacht Club. In the course of the Cup history, the club has often fiddled with the Deed of Gift that controls the terms of challenge, most recently in 1956, to allow Twelve-Metre boats in place of the giant J Class, and to strike out the clause that said challengers had to cross the Atlantic on their own bottoms. The club’s “Fortress America” policy in regard to the Hoboken tank seems more than a little bit “chicken.”